MONUMENTAL MEMORIALS

Death is a universal feature of human life, and all cultures have beliefs and traditions regarding death, burial, and remembrance. The American tradition of marking burials with stone memorials has captivated scholars from a range of disciplines for over a century, and many have explored what can be learned about individuals and societies by examining their memorials. Anthropologists have written extensively about ritual behaviors associated with death, the role funerary practices play in society, and the ethnographic importance of material culture in the context of burial. These anthropological perspectives are foundational to the field of cemetery studies and inform a large body of interdisciplinary research.

In the early 20th century, folklorists and art historians studied memorials as folk-art objects and focused their analysis on regional characteristics, literary content of epitaphs, and style of individual carvers. In the 1960s and 1970s, historical archaeologists James Deetz and Edwin Dethlefsen analyzed memorials through a structuralists perspective and connected changes in funerary iconography to changes in religious belief. They argued that 18th century changes in New England from traditional symbols, like death’s heads and cherubs, to popular symbols, like willow trees and urns, were the result of the secularization of society. Some researchers have refuted this assessment and suggest that changes in iconography had more to do with the personality of the carvers and less to do with religious beliefs of society at large.

Cemetery studies grew in popularity during the second half of the 20th century, and scholars utilized new post-processual theoretical perspectives to answer research questions regarding class, ethnicity, gender, and race. In the late 19th century, cemeteries became repositories for mass produced objects of mourning culture which represented middle class sentiments and values. These objects are a visual representation of hierarchical social order and class distinction at the turn of the century. Immigrant communities adopted local mourning symbols as they assimilated into American culture. Even followers of Reform Judaism incorporated these new symbols into their funerary art despite Hebraic taboos against graven images.

During this period, many common motifs embodied and glorified values of domesticity and kinship. Rustic styles represented the values of family, home, and religion. Floral motifs carried an implication of gendered meanings that can be understood through analysis of popular literature. Memorials in African American communities were less influenced by 19th century commercial trends, and Black artisans utilized a variety of materials and objects with symbolic and aesthetic value when creating these exceptional examples of vernacular art.

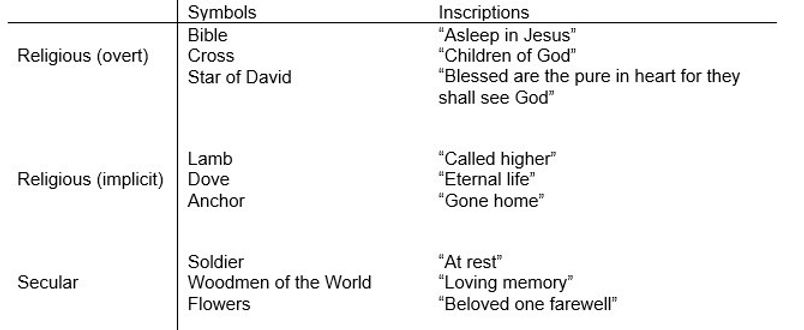

The increasing secularization of modern society resulted in an observable decrease of religious symbols on memorials in the 20th century. The spiritual meaning of mortuary iconography is not always possible to determine, but generally falls into the category of overtly religious, implicitly religious, or secular. Though rural cemeteries were ostensibly non-denominational, the prevalence of traditional Christian iconography created a self-styled religious environment. In the 1850s, about one third of memorials had religious motifs, however, during the first decades of the 20th century, prevalence of religious motifs decreased to about one in ten.

Chart: Religious and Secular Motifs